With the arrival of summer, the Delaware Department of Agriculture (DDA) Forest Service and Plant Industries sections would like to alert homeowners, campers, and tree care professionals to look for signs or symptoms of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis), otherwise known as EAB, a destructive wood-boring pest of ash trees (Fraxinus species). At the same time, DDA is beginning its own annual surveillance to look for EAB in the First State. Survey methods include two types of baited lure traps, visual inspections, and even “bio-surveillance” – which uses a native ground-nesting wasp (Cerceris fumipennis) that feeds on beetles similar to EAB. Past experience has shown that the effort will not be easy.

According to Jimmy Kroon, State Survey Coordinator for DDA’s Plant Industries section, EAB is “a very difficult insect to contain… The exit holes are very small – less than half a centimeter wide – and the beetles are very small, so it’s hard to see.”

Watch a video of DDA staff looking for emerald ash borer in New Castle County and setting up EAB traps.

What is emerald ash borer?

The emerald ash borer is a small, green beetle that belongs to a large family of beetles known as the buprestids, or metallic wood boring beetles. The description is apt, as many of the adult buprestids are indeed glossy, appearing as if their wing covers are made of polished metal. The emerald ash borer, with its green, iridescent wing covers, fits right in. Adult EABs are relatively slender and between 0.3 to 0.55 inches in length – small by most standards but large compared to other buprestids.

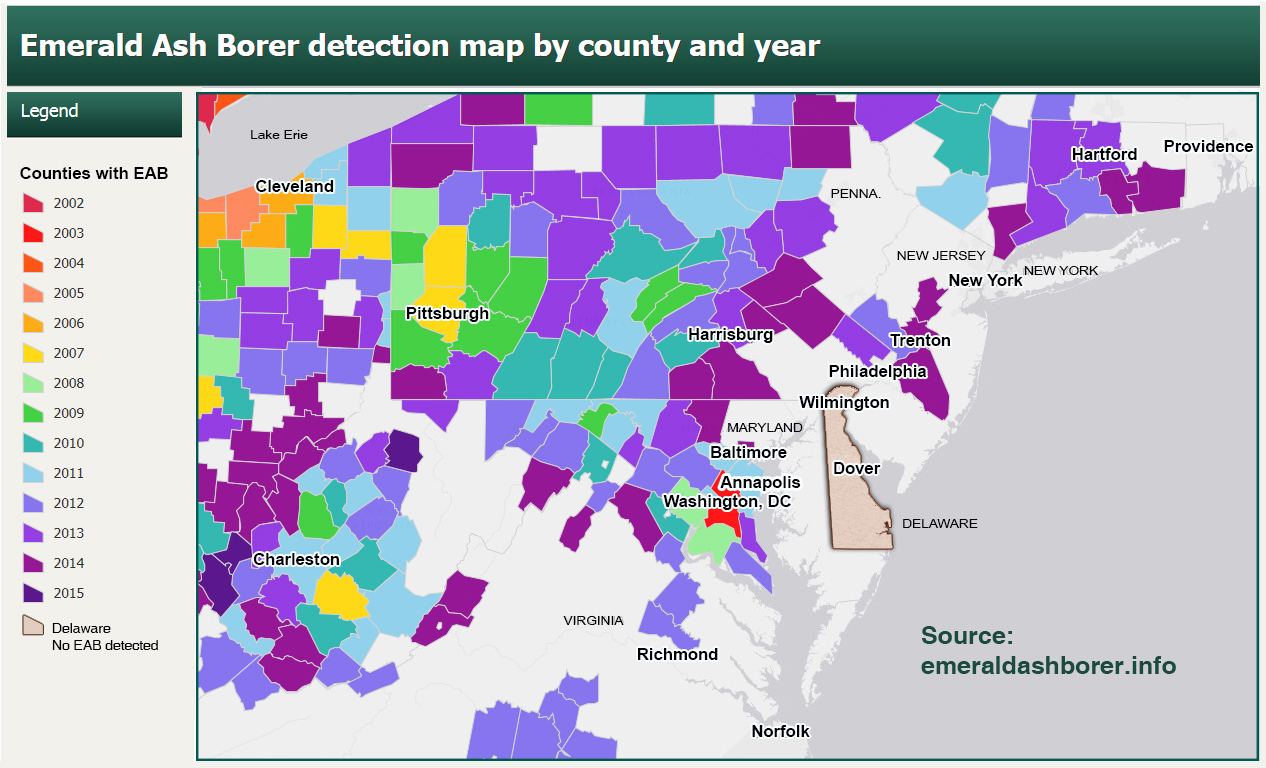

Native to Asia, EAB was unknown in North America until its discovery in southeast Michigan in 2002. Since then, EAB has killed millions of ash trees, with numbers rising every year. The most recent map issued by the USDA’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) shows that EAB has been found in 25 states, including those in the Mid-Atlantic nearest to Delaware (Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia). The nearest known location of EAB to Delaware is in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, just north of Philadelphia. EAB has not been detected in Delaware, though an intense surveillance program has been ongoing for nearly 10 years. Its discovery would likely trigger a federal quarantine by APHIS, similar to other parts of the country.

The potential for damage is very high. A previous study by the U.S. Forest Service once estimated that the ongoing EAB infestation could have “an estimated cost of $10.7 billion” nationally. In Delaware, ash are relatively minor components of the native forest, found mainly in streamside areas and flood plains. In some urban areas such as the Sharpley and Tavistock neighborhoods near Wilmington, ash is the predominant large street tree and for this reason EAB is considered a serious threat to urban forests.

Surveillance for EAB: Purple Traps, Green Traps, Visual Surveys, and “Bio-Surveillance”

For many years, the most visible survey method for EAB has been the “purple panel trap,” a three-sided box with openings at the top and bottom and sticky surfaces that contains a pheromone lure attractive to EAB. This year, in addition to 53 of the purple traps, a new green Lindgren funnel trap will be used in nine locations. Its bright green color was developed by researchers at the USDA.

“The color is something that emerald ash borer really likes. They’re attracted to it,” said Jimmy Kroon, State Survey Coordinator for the APHIS Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) and its Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) Program. “It’s baited with the same lures as the purple panel trap that we’ve been using for a few years, but reports are that this trap has much higher catch rates than the purple panel traps. Hopefully it will make a better detection tool.”

DDA staff started putting out traps at the beginning of May and they will be taken down by late-August.

“The trap is coated with Fluon, which is a white slippery material, and so the beetle is attracted to it because of the color and the lure. [EAB] basically falls down through the holes in the centers of the funnels into this cup [which is] filled with glycol. And so the beetle falls in there and dies,” Kroon said.

Last year, the green trap was used on an experimental basis but achieved solid success rates.

“They were collecting pounds of emerald ash borer in the collecting cups, so that’s definitely a lot more than we’ve been collecting in the purple panel traps,” Kroon added. Helping Kroon is Jillian Dixon, a DDA environmental scientist who worked on the Asian Longhorned Beetle outbreak in Massachusetts. While ALB is a much larger pest that feeds on a wider range of trees, it expands its range slowly, which has led to successful eradication in some areas.

Conversely, EAB has never been successfully stopped anywhere in the United States. Once it is detected, the focus has always shifted to management and not eradication.

In response to the EAB threat, officials are working with federal and state agencies, public and private partners, municipalities and homeowner groups to inform the public about EAB and what steps should be taken to prepare for its eventual arrival.

The following are some key recommendations for affected groups:

Homeowners:

- Find out if you have ash on your property and monitor trees for signs of poor health or damage according to this fact sheet on EAB.

- If you have ash trees on your property, consult the Delaware Forest Service’s latest recommendations on managing ash trees for Emerald ash borer.

- Don’t plant ash if you are considering a new tree for your property (instead, check out the Delaware Forest Service “Recommended Trees“ list for suggestions on finding the “right tree for the right place”.

- Stay up-to-date on EAB in your area by checking out the following websites: emeraldashborer.info, stopthebeetle.info and hungrypests.com

Municipalities:

The Delaware Department of Agriculture’s Plant Industries Section has issued a Resources Guide to help cities and towns make preparations for EAB. The guide contains links to plans developed for cities than can expect to become infested within the next five to ten years. The goal is to limit sudden financial impacts by spreading control costs over several years. The recommendations are based on EAB Plans developed by four different cities. Two methods are used which work together:

- Begin removing ash trees early to reduce inventory, and

- Apply chemical treatments to some trees to prevent infestation.

Question: My ash tree looks fine but EAB has been detected in the vicinity of my property. Should I start treating my tree?

Right now, EAB is more than 15 miles away from Delaware. According to the resource guide, Insecticide Options for Protecting Ash Trees from Emerald Ash Borer, “Detecting new EAB infestations and identifying ash trees that have only a few larvae is very difficult. Ash trees with low densities of EAB larvae often have few or even no external symptoms of infestation. In addition, scientists have learned that most female EAB lay their eggs on nearby trees, i.e. within 100 yards of the tree from which they emerged. A few female beetles, however, appear to disperse much further, anywhere from 0.5 miles to 2-3 miles. Therefore, if your property is within 10-15 miles of a known EAB infestation, your ash trees are probably at risk. If your ash trees are more than 10-15 miles beyond an infestation, it is probably too early to begin insecticide treatments. Treatment programs that begin too early waste money and result in unnecessary use of insecticide. Conversely, treatment programs that begin too late will not be as effective.

Early summer is the time when EAB adults could begin emerging from an ash tree, which is why homeowners and property managers need to know if ash is present on their property and should visually inspect trees for potential health issues and signs of damage. With every type of ash species susceptible to the emerald ash borer, this short video field guide on YouTube can help in identifying ash trees by the branches, bark, and leaves and indicate if EAB is present.

As a hardwood with a high heat value, ash is also ideal for firewood. Unfortunately, this is one of the primary means for the insect to travel to new locations. Because EAB has been spread through the movement of firewood, summer is a good time to remind campers and travelers of the national “Don’t Move Firewood” campaign which explains the importance of buying and burning local firewood, which should be from a few miles away or at least in the same county.

EAB is so aggressive that many ash trees can die within two or three years of becoming infested. In the eastern United States, ash trees are important both ecologically and economically. Ash is highly desirable for urban tree plantings and the wood is valued for flooring, furniture, and sports equipment such as baseball bats and hockey sticks. During their larval stage, EAB feed under the bark of ash trees. This activity damages, and eventually kills, the trees. EAB adults mate shortly after emergence in the spring. Each female can lay 60-90 eggs in their lifetime and eggs typically hatch in 7-10 days. Minute larvae bore through the bark and feed on the nutrient-rich phloem. Larvae continue development into early fall. In the spring, EAB pupae start to transform into adults and in one to two weeks a new generation of EAB adult beetles emerge through D-shaped exit holes. Adults are most active on clear, calm days and are likely found on the warm, sunnysides of the trees. Adult EAB live two to three weeks.

In the United States, only ash trees are at risk for EAB. However, ash is widely distributed and all 16 native ash species are susceptible to attack. Ash trees with low population densities of EAB often have few or no external symptoms of infestation. Symptoms of an infestation may include any or all of the following: dead branches near the top of a tree, leafy shoots sprouting from the trunk, bark splits exposing larval galleries, extensive woodpecker activity, and D-shaped exit holes (Please see this fact sheet on EAB.).

Adding to the risk for ash trees, EAB is not the only insect pest that can attack them. Several other borers also target ash species and the extensive damage they cause can mimic symptoms of an EAB infestation. At Gracelawn Memorial Park on DuPont HIghway in New Castle, Jimmy Kroon and Jillian Dixon of the DDA Plant Industries Section met with Pete Kingshill of Bartlett Tree Experts and Joe Casavant, Park Superintendent. The rapid decline of several ash trees – characterized by branch die-back, epicormic sprouting (a flush of new growth to compensate for a tree’s injury), and exit holes on the bark – had the makings of a suspected EAB attack. However, closer inspection revealed what turned out to be native ash bark beetles attacking a tree already stressed by environmental factors.

Similarly, staff from the Delaware Forest Service recently inspected trees in the Tavistock neighborhood near Wilmington that were slated for removal. Though the trees were clearly in decline, there was no visible sign of EAB. Likewise, forestry officials recently looked at the decline of young ash trees on a street in a new development in Middletown. With all the markings of an insect attack present (branch die-back, sprouting, exit holes), a more thorough inspection indicated that the holes on the bark were larger than EAB would produce, likely an attack by some type of native clearwing ash borer, which causes similar symptoms but leaves much larger round exit holes instead of the smaller D-shaped holes made by EAB.

The differences between native borers and the Emerald ash borer are available on this fact sheet issued by The Ohio State University Extension. For more information:

- Jimmy Kroon, State Survey Coordinator, DDA Plant Industries, 302-698-4586, jimmy.kroon@delaware.gov

- Bill Seybold, Forest Health Specialist, Delaware Forest Service, 302-698-4553, william.seybold@delaware.gov